From a brilliant article on the politics of the new Egyptian Museum by

Mohamed Elshahed, published at

Jadaliyya (one of the best Middle East blogs, period). It's an indictment of the security mindset, slavish devotion to foreign mass tourism, and contempt for ordinary people that has characterized Egypt's heritage establishment for the last generation. Long excerpt follows,

read it all here:

The Egyptian state has been firmly in control of archaeology and of the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities for several decades. Egypt’s first and only Minister of Antiquities, Zahi Hawass, personifies the notion that Egyptians are in control of their ancient heritage, previously dominated by Europeans. This control has translated into security-oriented policies that claim to protect artifacts from theft and vandalism. In reality, this has meant protecting artifacts from Egyptian masses, while making them available to tourists. The government has not capitalized on Egypt’s material legacy as a cultural resource central to discourses on national identity and heritage. The Supreme Council of Antiquities’ main goals have been security not accessibility and mass tourism not culture.

My first visit to the Museum as an adult was in 2006, when a friend was visiting Cairo from the United States. As we approached the security checkpoint, a foreboding first encounter with a cultural institution, identification was requested of us. I had never been asked for identification to enter a museum anywhere else in the world, let alone the most important museum in my home country. While she had no problem entering, being American, I was questioned about my relationship with my friend and my reasons for entering the museum. As an Egyptian, who is not a tour guide, I was treated as an object of suspicion.

|

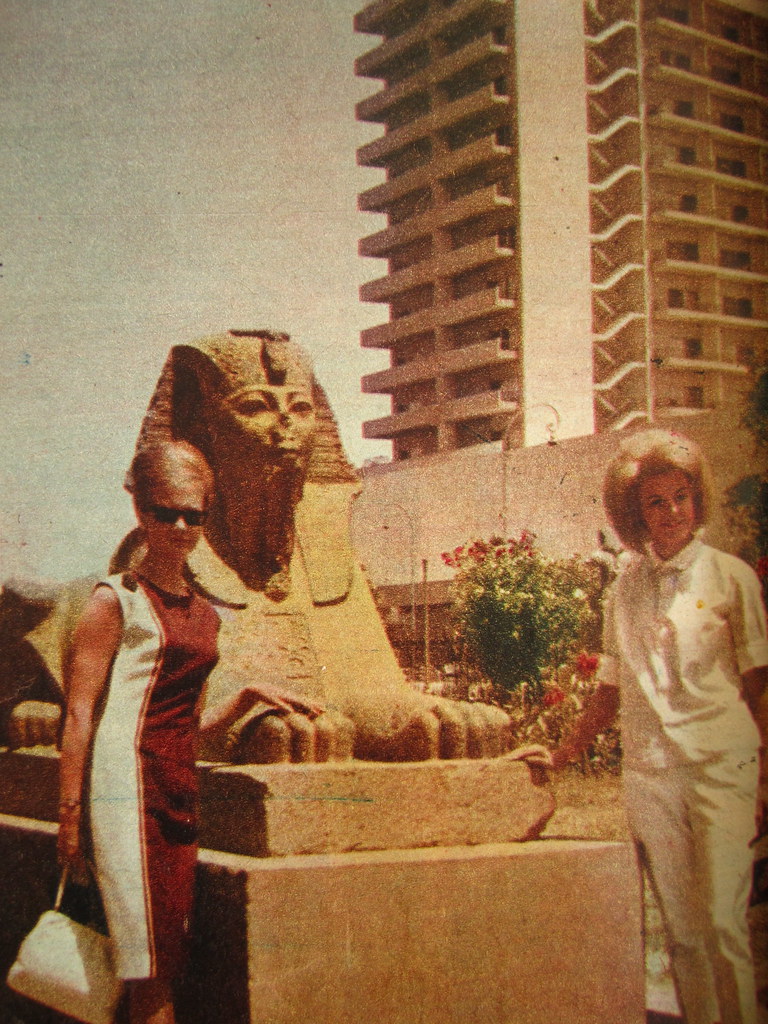

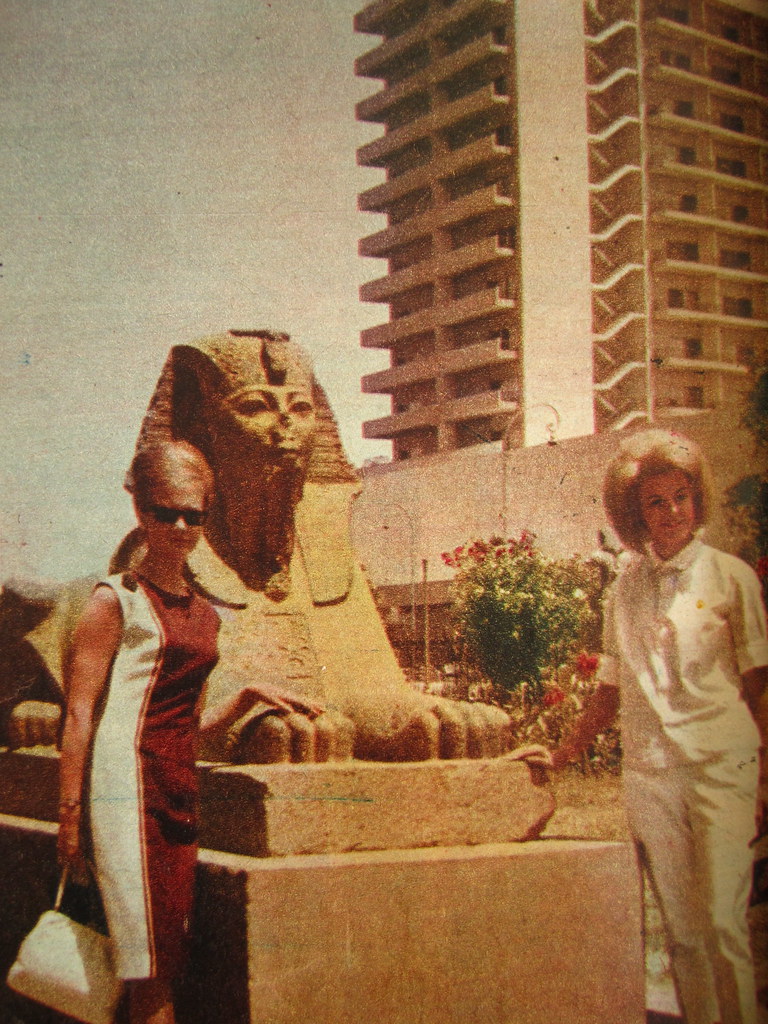

| The real audience for Egypt's antiquities? (elshahedm on Flickr) |

This visit made clear to me that the purpose of the Egyptian Museum is purely touristic. Museums have become fortified storehouses for badly labeled, disorganized artifacts meant to be consumed purely as objects with little historical significance besides their apparent old age. Tourists are meant to be the prime consumers of these objects, as they pay seventy to one hundred pounds to enter in contrast to Egyptians who are charged a few pounds.

Adding insult to injury, during the Tahrir protests of 9 March, the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities became known as salakhana: the torture chamber. Military police used the museum as a command center, due to its secure location, where they held, interrogated, and tortured protesters. The single most important museum in the country with Egypt’s most valuable artifacts was transformed into a place where Egyptians were beaten and humiliated.

...

There is no excuse for Cairo’s Museum of Egyptian Antiquities’ current condition with peeling paint and missing artifacts replaced by hand-written notes saying in Arabic “under restoration” or “in a traveling exhibition.” The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities is in need of serious remodeling and expansion. This surely will be expensive and will need a grand vision to transform and update this important institution of world heritage.

However, the recent drastic decision to move this urban institution out of the heart of the city and into the desert two kilometers from the Pyramids is a calamity and a disgrace. To signal the decision, in 2006 the red granite colossus of Ramses II that adorned central Cairo since 1955 was removed to a storage facility at the city’s edge, where it awaits a new home in the proposed Grand Egyptian Museum.

Public museums are fundamentally urban centers firmly tied to their metropolitan contexts. The mere visibility of Paris’ Louvre pyramid and inside-out Pompidou Center or New York’s Metropolitan Museum in their urbane settings is as important as the contents of these world-famous buildings. The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities is forever associated with its Tahrir Square location, especially after the well-photographed and documented uprising that took place at its doorstep. Moving the museum into a desert location outside the city center serves the museum’s current priorities of security and tourist exclusivity. Are these still the priorities of Egypt’s leading museum in light of the unfinished and ongoing uprising?

Interesting and provoking piece; however, saying that a museum should be placed in the centre of a city has rarely been a priority for museum builders or directors.

ReplyDeleteThe British Museum was built in the 'countryside' of Bloomsbury in the 1750s; 100 years later the fields of South Kensington were used for the Victoria and Albert Museum, as it was thought that the clean air there would preserve the objects. At the same time the Metropolitan Museum was built in the uninhabited and largely unfashionable Upper East Side of Manhattan.

Also, The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities has never been "forever associated with its Tahrir Square location". It is the third site for the museum in its 150 year history. It has moved from Boulaq to Giza (where the Grand Egyptian Museum will be built), and thence to Tahrir.

The Grand Egyptian Museum may now be on the fringes of Cairo (as it was before!), but - as happened in Bloomsbury and the Upper East Side - the city will keep growing. It is also next to the Pyramids, which are visited by rather more Egyptians than foreign visitors.